Is 3D the future of mobile gaming?

Top games developers tell us the argument's not so two-dimensional

With 3D graphics, video games came of age. 3D opened the door – literally – to another dimension, an imaginative universe that gamers could inhabit and explore, rather than a world they passed through on rails. As soon as 3D technology became available in mainstream games, developers and gamers embraced it so fully that 2D became a niche almost overnight, albeit one revived years later on the relatively weedy mobile phone.

However, things are moving on. If you've obtained a contract phone at some point over the last 12 months, the chances are you own a gaming machine more powerful than every portable console up to the Nintendo DS, capable of producing 3D graphics that would look at home on an original PlayStation.

Surprised? No wonder: 3D games are struggling to find a place in the mobile gaming mainstream. While a few developers like Polarbit and Fishlabs are working almost exclusively with 3D, and others are adopting it with increasing confidence – Glu, I-Play and Digital Chocolate, which is reworking its 2D classic Rollercoaster Rush for 3D, as pictured, for instance – many developers are reluctant to change gear.

Before we start to search for the reasons, we need to chart the landscape, beginning with the foggy territory of mobile platforms.

Technically speakingJava 2 Runtime Edition is the platform on which almost all games in the UK are made, and, unfortunately, it's also the feeblest. Although 3D games in Java are improving, it's the Vauxhall Corsa of platforms: affordable, ubiquitous, and indifferent.

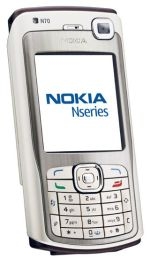

Symbian is a more powerful platform, for more powerful phones, and so its games are larger and more expensive than Java's (similar is the BREW platform in the US). If you don't own something like a series 60 Nokia, you're pretty much out in the cold; but if you do, you have access to some stunning 3D graphics.

Symbian is a more powerful platform, for more powerful phones, and so its games are larger and more expensive than Java's (similar is the BREW platform in the US). If you don't own something like a series 60 Nokia, you're pretty much out in the cold; but if you do, you have access to some stunning 3D graphics.

In the UK, mobile gaming takes place almost exclusively on these two platforms, but there are several obscurer alternatives. (For a comprehensive overview, read Mike Abolins's definitive Pocket Gamer guide.)

Aside from the relative weakness of the Java platform and many of the handsets for which games are being made, there are several other problems for 3D mobile gaming to overcome. Speaking to Pocket Gamer, Glu's Chris White and Digital Chocolate's Trip Hawkins provide an insight into the economics of 3D development.

"3D titles are more expensive to develop than 2D titles," Chris White explains. "We've seen team sizes double on recent 3D projects, with art and design being the most resource intensive areas."

And not only do 3D games cost more to make; the target audience (those with sufficiently powerful handsets) is much smaller than that for 2D.

On top of this, 3D mobile game creators have to deal with the perennial difficulties that all mobile game developers face: fragmentation and control. Not all handsets are born equal, and programmers are constantly under pressure to produce games that both impress on high-end handsets and run adequately on older models.

As White says, speaking from experience: "a great high-end version really puts pressure on us to ensure the low-end version is equally amazing."

Digital Chocolate's Trip Hawkins expands upon the point: "3D development is more expensive, and mobile phone operators need to devote special merchandising attention to 3D games so they don't get mixed in with everything else."

Then there's control. Most current 3D mobile titles are racing games, for the practical reason that only three or four buttons are required to steer the car, brake, and in some cases deploy powerups. A console title like Legend of Zelda: The Ocarina of Time, which makes use of all 14 buttons and the analogue stick on an N64 controller, would be massively diminished on a current handset.

Then there's control. Most current 3D mobile titles are racing games, for the practical reason that only three or four buttons are required to steer the car, brake, and in some cases deploy powerups. A console title like Legend of Zelda: The Ocarina of Time, which makes use of all 14 buttons and the analogue stick on an N64 controller, would be massively diminished on a current handset.

Analogue controls and 3D games grew up together, and it's difficult to conceive of one without the other. The graphical capabilities of mobile phones will inevitably reach a uniformly high-end state, but, short of a complete revolution, the issue of control will always loom over mobile gaming.

3D or not 3D?Despite these setbacks, 3D is a selling point, and ambitious developers are always keen to add a third dimension. However, this sometimes works to the detriment of the product. 3D Worms Forts, for instance, dispenses with deformable terrain in order to create perspective depth, and the result is a weaker game than its humbler predecessors. THQ exchanged a gameplay dimension for a visual one.

Writing about an early 3D game called Breathless in 1995, Amiga Power journalist Stuart Campbell declared, "this would be rubbish in 2D, so it's rubbish in 3D". At a time when the desire to be technically impressive can cloud a developer's judgement, this is still a useful principle to bear in mind.

Given all these difficulties, one feels compelled to ask the question: is it worth it? Should developers learn to accept the limitations of the mobile phone and confine themselves to simpler, smaller games that make best use of the hardware? As I-Play's David Gosen remarked in a recent interview , "it's not about Halo or GTA: Vice City on the mobile. It's about games that fit the device. If you understand the constraints of the mobile then you can build an excellent game to fit."

Digital Chocolate's president of studios Ilkka Paananen gave us his own insight into the merits of 2D: "Over 25 years of the PC increasing in processing power, it took a game like The Sims to come along and break through to the mass market, with a 2D isometric graphics engine. Not 3D."

Hawkins illustrates the point neatly: "As a point of comparison, consider that 3D goggles appeared in movie theaters 50 years ago. Movies were good enough without it, as well as being simpler and more convenient with no goggles. So it never caught on."

Certainly, there's evidence that 3D graphics are no longer a minimum requirement in order for a game to succeed. The use of cell-shading in home console titles like XIII, The Legend of Zelda: Windwalker and Okami show that there's demand at least for the look of 2D, if not the feel.

2D still has a place in the 21st Century The graphical arms race is singularly a Western phenomenon, and in terms of technology, we can learn a lot from the Japanese.

The graphical arms race is singularly a Western phenomenon, and in terms of technology, we can learn a lot from the Japanese.

In 2003, Disney announced that it would make no more 2D animated films because the bulbous 3D characters of Toy Story and Monsters Inc had made them obsolete.

In the same year, Hayao Miyazaki unveiled the majestic Spirited Away to UK audiences and put Disney's entire output to shame.

In the field of gaming, meanwhile, the most stridently Japanese hardware to have appeared in the last couple of years – the DS and the Wii – are also technically the feeblest, and they have comfortably wrestled sales from their more muscular competitors.

During the early '90s, when Nintendo's Shigeru Miyamoto was asked to use exciting new pre-rendered 3D graphics in his game Yoshi's Island, he refused. Instead, he created a childish, crayon-drawn identity for his platform masterpiece, apparently to make a point: beauty and power aren't the same thing.

During the early '90s, when Nintendo's Shigeru Miyamoto was asked to use exciting new pre-rendered 3D graphics in his game Yoshi's Island, he refused. Instead, he created a childish, crayon-drawn identity for his platform masterpiece, apparently to make a point: beauty and power aren't the same thing.

The ethos at Digital Chocolate, meanwhile – a purveyor of many well-received 3D titles – emphasises the greater importance of mobile's social element. "To make mobile a first-rate platform," Paananen says, "we believe mobile gaming needs something that will connect users to each other emotionally." The real third dimension is social, not spatial.

Speaking with Pocket Gamer, I-Play's Leighton Webb described the commercial dimension of the issue.

"The console industry has consistently demonstrated how to leave 'dollars on the table'," Webb says, "by leaving existing technology behind too soon because the minority hardcore niche and occasionally bored developers want deeper, more challenging, supposedly graphically superior experiences."

3D on track for nowStill, progress is inevitable, and mobile can't afford to bow out of the race entirely. Blade's Peter Jones exclaimed with disbelief in a recent interview: "there are still so many mobile game development studios that don't do 3D. I mean, for God's sake, what are they thinking?"

Remaining loyal to 2D is all very well, but no developer can afford to let the river of progress flow around them. They have to swim, or they'll sink.

But ultimately, 3D is just another tool in the game maker's toolbox. "There are genres that benefit from a fully 3D world," says Chris White, "but 3D shouldn't be used for the sake of it. On the DS, no one cares about rendering technology, just whether the game is fun." And everybody we spoke to agreed.

The righteous path, as with all technology, is to use what you have wisely, and in the field of games for developers to make sure that gameplay is the central consideration. The message we're getting is that developers are well aware of what makes a great game, and what significance 3D holds for the industry.

In the end, whether to use 3D must be an artistic choice, rather than one driven by a perceived necessity to keep up with the times. And the encouraging – and, perhaps, surprising – thing about mobile gaming, is that its artists have the power at their hands to make that choice.