What's the story behind Microsoft's handheld Multi-Component Gaming System patent?

Or how to get consoles, phones, PDAs and gaming handhelds to play together

Having spent the weekend elbow-deep in the US Patent & Trademark Office's website, we now know inventing things isn't about absent-minded eccentrics cooking up weird gadgets in their garden sheds. The world of inventions has become the preserve of lawyers and accountants.

The context for this discovery was the Patent Office's publication of a proposal Microsoft submitted on the subject of a Multi-Component Gaming System, a fact first picked up on by Unwiredview. The patent's not yet been granted – a point we'll come back to later – but this is the first time it's been publicly available since it was filed on the 14th October 2005.

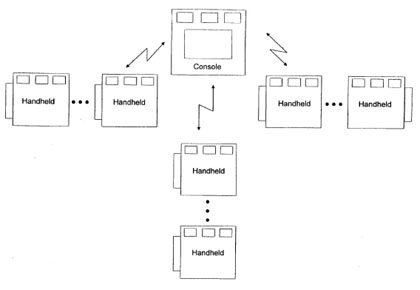

One console, lots of handheldsThe basis of the patent is for a system in which a non-portable gaming device (such as a console, PC or laptop), and several portal devices (such as phones, PDAs and dedicated gaming handhelds), can work in a co-operative manner using either wireless or wired connections.

The main focus is that such a Multi-Component Gaming System will allow the handheld devices to gain access to additional features, such as the extra processing power or memory of the console, or access to the peripherals connected to the console, such as a monitor or a home theatre system.

It's sort of like an extension of what's known as 'distributed processing,' where different parts of a program run simultaneously on two or more computers that communicate over a network, into what could be called 'distributed gaming'. There are some subtle differences, however, since the flow of information isn't just directed to the handhelds using the console, but vice versa too.

In terms of how this might work in practice, paragraph 0012 states: 'the software residing on the handheld gaming device is flexible and scalable enough to utilize and benefit from software residing on the console gaming device. Similarly, software residing on the console gaming device is flexible and scalable enough to utilize and benefit from software residing on the handheld gaming device'.

Examples vary from the simple, such as backing up handheld save games on the console, to the more complex, such as the handheld device being used to process video data that is then streamed back to the console to be integrated into the final rendering of the game for display.

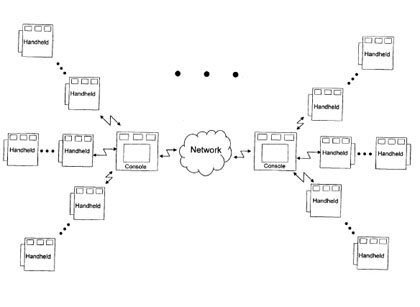

Perhaps most interesting is the potential when more than one 'system' (which consists of at least one console and one handheld) is linked together, as shown above.

One novel example of how different handheld devices can work together given is where one handheld downloads additional audio effects from another handheld device that isn't within its own Gaming System, but is connected via the network (in the diagram, the device in the bottom right corner accessing information from the one in the top left corner, for example). This approach could also be used to distribute game updates or patches in a large-scale adhoc fashion.

What does it mean for Xboy?As is typical in such patent examinations, Microsoft's submission poses more questions than it answers. The most obvious question is whether the patent means Microsoft will be launching its own dedicated handheld device, which will integrate within the wider world of Xbox Live and the company's other services, such as the unified XNA game development tools?

Of course, that the patent defines handheld devices as being everything from PDA to mobile phones and dedicated gaming portable means it's impossible to tell. (UnwiredView sees the proposed gaming service for the company's Zune MP3 player as an obvious tie-in.)

Another reason it's difficult to draw too many conclusions from this filing is that companies attempt to make their patents as broad as possible to limit their competitors. If a patent is granted, no one else can use that technology or knowledge without permission and payment of a license fee for either 17 years from granting of the patent, or 20 years from the earliest filing date, whichever is longer.

The trouble for Microsoft might be we can think of several examples of gaming system that have already used such techniques: so-called Prior Art.

Sony demonstrated the use of a PSP acting as a rear view window for the Formula One PlayStation 3 game, for example, though that was in 2006, after Microsoft's filing. Nintendo's long had connectivity between its consoles, however. To pick one example, games such as 2003's Final Fantasy: Crystal Chronicles enabled four players to connect Game Boy Advances to the GameCube to control characters and display other information.

There have also been plenty of peripherals that enable you to connect gaming handhelds such as the GBA to TV screens. Presumably the additional detail of connecting more than one Gaming System together is something Microsoft thinks makes an important difference.

Xboxing clever, but no knockoutMore generally, the patent demonstrates the feverish ongoing interest in creating unified gaming networks that enable the sort of pervasive gaming where the game and the players' experience matters more than the hardware. And Microsoft's certainly been working hard at that area.

Another filed-but-yet-to-be-granted patent from 2004 [number 2006-0068910, Game console communication with a device, and as seen below] outlines the ability to connect handheld devices such as mobile phones, PDAs and MP3 players to the original Xbox console.

.jpg)

Of course, this is also a warning not to draw too many conclusions from any particular filing. Microsoft never deployed such a system (although Sony did offer some limited PlayStation 2-mobile phone connectivity in Japan).

Sometimes, thinking up a clever idea and even getting patents is the easy part. Making them work in the real world is a different story.

See more of our recent features here.